The Tree

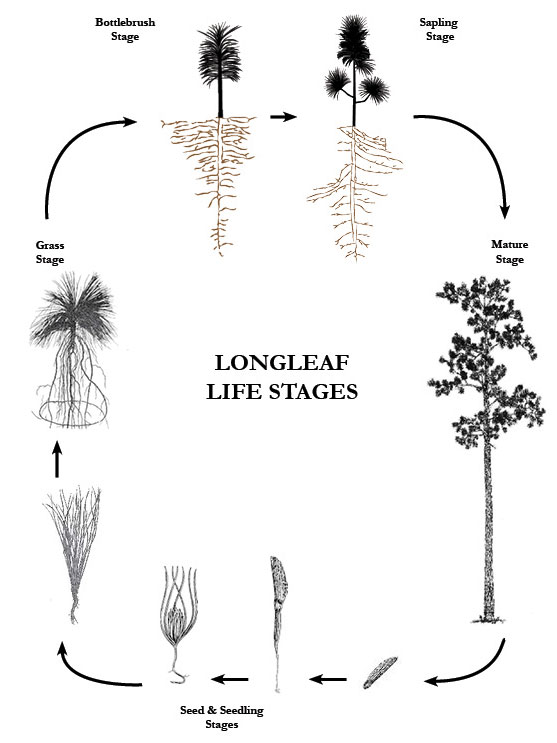

Life Stages

Longleaf pine is the longest-lived of the southern pine species. Individual longleaf pines can reach 250 years in age (with trees in excess of 450 years old documented). To reach that point of old age the life history of longleaf pine can be described in several stages.

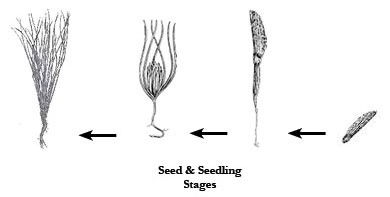

Seed

Falling from the tree’s cones in October to late November, longleaf seeds whirl to the forest floor but generally do not fall far from the tree due to their large size. Longleaf pine seeds are high in fats and are thus highly prized by seed predators like mice, birds, squirrels, and ants.

Seeds that escape predation germinate within a few weeks once there is adequate soil moisture. Although seeds will germinate almost anywhere (on rocks, logs, forest mulch), they generally need to land on mineral soil to survive subsequent droughty periods.

Seedlings

New germinants will hang on to the wing from their seed as they start to show needles. The wing will eventually fall off as the needles push through. During this first stage, the seedlings are very susceptible to fire, drought and predation and will take upwards to a year to reach the next life stage.

The Grass Stage

This unique stage of a longleaf pine's life history resembles a clump of grass more than a tree, hence the name “grass stage.” The young trees will not grow in height; instead, grass stage longleaf focus their growth underground to develop an impressive root system.

During the grass stage, a thick cluster of needles protects the growing tip (bud) while the tree remains at ground level. If a fire occurs, the needles may burn but the tip of the bud remains protected. New needles quickly replace those that were burned off. During the grass stage, longleaf pine seedlings are very resistant to fire damage.

The grass stage may last anywhere from one to seven years depending on the degree of competition with other plants for resources. Rare instances of 20 years have been documented.

The Bottlebrush Stage

When the root collar diameter (that area right at ground level) reaches 1 inch in a grass stage longleaf, the young tree will initiate height growth. Beginning in February to mid-March, a single, white growing tip will emerge upwards from the protective sheath of needles. This white tip, called a candle, may grow a few feet in just a few months. Green needles will then emerge from the candle and the candle will turn scaly and brown as bark begins to form. Without any horizontal branching, the tree resembles a bottlebrush.

By growing rapidly in a short period of time, the young tree increases its competitive advantage for sunlight and moves its growth bud above typical flame heights if a fire were to occur. However, during this stage of growth, longleaf pine trees are slightly more vulnerable to fire as it may take a year or so before the bark thickens enough to withstand most fires. The longleaf may remain in this stage for a couple of years.

The Sapling Stage

Once the longleaf bottlebrush reaches about 6 to 10 feet in height, lateral branches begin to emerge and signal the beginning of the sapling stage. Around late February to mid-March, white growing tips or candles can be seen extending upwards from the tufted needles at the end of the branches. The tree continues to grow in height at upwards of 3 feet per year.

As the tree grows taller and the bark becomes thicker, the longleaf becomes less susceptible to fire. After the tree reaches 8 feet in height and about 2 inches in diameter at ground level, it becomes very robust and is rarely killed by fire. The tree will remain in this stage for several years.

The Mature Stage

Somewhere around 30 years after height growth initiation, longleaf pines begin to produce cones with fertile seeds. As the forest begins to mature, lower limbs may be shed or pruned off by fire. The trunk of the tree begins to fill out into a straight, relatively branch free tree that resembles a living telephone pole (in fact, many longleaf pines are sold for telephone poles).

On more fertile soils, the tree may continue to grow in height up to 110 feet. On poorer soils, the tree may only grow to 60 feet. After about 70 -100 years longleaf essentially ceases height growth. During the later stages of this period, trees may begin to show signs of decay and rot. In particular, longleaf pines reaching 80 years in age may become infected with a fungus called red-heart that causes the otherwise dense heart of the tree to become punky, soft, sappy and full of small channels.

Old-Growth

Large-diameter trees with flat-topped crowns dominate the forest. Historical accounts describe mature longleaf pines in excess of 120 feet tall and 3 feet in diameter. Conventional wisdom suggests that old-growth longleaf pine trees stop growing at these advanced ages. However, many instances exist where old-growth longleaf pine trees have actually increased growth rates at 200 years (+) when resources became available. At older ages, more and more trees begin to show signs of internal rot from red-heart fungus. In some localities, as many as half the trees per acre can be affected with red-heart in the crowns.

Research has shown that although a longleaf forest looks like and is defined as an "old-growth" stand (i.e., large, scattered, old trees) it still has approximately 2/3 of its trees less than 50 years old. Due to the large occurrence of small scale disturbances in longleaf pine ecosystems, the forest as a whole is transitioning through at least one of these stages of growth simultaneously.

Death

In a landscape that sees lightning, tornadoes, wildfires, drought, hurricanes, or even ice storms on a regular occurrence, it is really quite remarkable for a longleaf pine to die from old age. After 300 years, trees that survive everything that Mother Nature has to throw at them will eventually weaken and begin to lose the ability to fend off forest pests like black turpentine or southern pine beetles. Slowly the trees begin to die off. The initial signs of this weakening include a thinning of green needles in the tree crown, followed by signs of beetle activity on the bark, then wilting of needles and finally by complete defoliation.

Usually when we think of the contribution of an organism (like a longleaf pine) to an ecosystem, we focus merely on the living organism. However, a longleaf pine is perhaps just as significant to the ecosystem after the tree is dead as when it is alive. Once the tree dies, its bark quickly sloughs off or is torn off by foraging woodpeckers. What remains is the white skeleton of the tree; known as a snag. Snags typically remain for only a few years; without the protective bark in place, the resinous inner wood of the longleaf is exposed and often causes the snag to ignite during a forest fire and burn to the ground.